Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disease characterized by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue. At a given age, bone mass results from the amount of bone acquired during growth, i.e. the peak bone mass minus the age-related bone loss which particularly accelerates after menopause. The rate and magnitude of bone mass gain during the pubertal years and of bone loss in later life may markedly differ from one skeletal site to another, as well as from one individual to another.

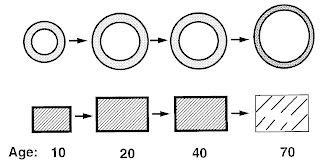

Figure 1. Schematic representation of cortical and cancellous bone changes throughout life. Stippling represents cortical porosity and hatching represents cancellous bone network.

Figure 2. Mean ± S.E.M. bone mass gain of the lumbar spine during adolescence (A: lumbar vertebrae L2–L4 BMD; B: lumbar vertebrae L2–L4 BMC). Reproduced with permission from Theintz et al. (1992).

Bone mass gain is mainly related to increases in bone size, that is in bone external dimensions, with minimal changes in bone microarchitecture. In contrast, postmenopausal and age-related decreases in bone mass result from thinning of both cortices and trabeculae, from perforation and eventually disappearance of the latter, leading to significant alterations of the bone microarchitecture (Fig. 1).

Peak bone mass acquisition

Before puberty, there is no consistent genderrelated difference in bone mass at any skeletal site

Indeed, there is no evidence for a gender-related difference in bone mineral density (BMD; g/cm2) at birth (Trotter & Dixon 1974), and this similarity in bone mass between males and females is maintained until the onset of pubertal maturation. During puberty, bone mineral mass of skeletal sites such as the lumbar spine more than doubles.

This increase occurs approximately 2 years earlier in females than in males (Fig. 2). Meanwhile, a gender-related difference in peak bone mass becomes detectable. This difference appears to result essentially from a longer period of bone mass gain in males than in females, resulting in a larger increase in bone size and cortical thickness in the former. Thus, the peak bone mineral content (BMC; g) at the lumbar spine and the proximal femur is higher in males than in females, whereas volumetric bone density (g/cm3) does not differ between genders at the end of pubertal maturation. On the other hand, black people have greater volumetric bone density than white individuals; trabecular number is similar, but the trabeculae appear to be thicker in black. Moreover, the cross-sectional area of the mid-femoral shaft is greater in black than in white individuals for an identical cortical.

"There is an asynchrony between the gain in statural height and the gain in bone mass". The peak of statural growth velocity precedes the peak of maximal bone mass gain. In males, the greatest difference occurs in the 13- to 14-year age group and is more pronounced for the lumbar spine and femoral neck than for the mid-femoral shaft, whereas in females it occurs in the 11- to 12-year age group, corresponding in both genders to pubertal stages P2–P3. In healthy Caucasian females with apparently adequate intakes of energy, protein and calcium, bone mass accumulation can virtually be completed before the end of the second decade at both the lumbar spine and the femoral neck. In males, cortical bone mass may still increase by a few percent beyond the age of epiphyseal plate closure.

Minggu, 03 Agustus 2008

Osteoporosis, genetics and hormones

Diposting oleh

Nutrisi Probiotik Burung

di

Minggu, Agustus 03, 2008

Label: Description of Osteoporosis

Langganan:

Posting Komentar (Atom)

Search

Categories

- bones (9)

- calcium (12)

- Description of Osteoporosis (1)

- HIV/AIDS (10)

- menopause (11)

- Osteoporosis (20)

- Stomach Diseases (5)

- vegetarian (9)

- vitamin A (5)

- Vitamin B (1)

- Vitamin C (2)

- vitamin D (5)

- Vitamin E (2)

- Vitamin K (1)

-

Recent Posts

0 komentar:

Posting Komentar